|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 77 |

Carlton B. Goodlett, champion of the people

by Thomas C. Fleming, Jun 4, 1999 Carlton Benjamin Goodlett, teacher, physician and publisher, was a native of Chipley, a small town in South Florida, of which I had never heard until I met Carlton on the campus of the University of California in 1935. He had just graduated from Howard University in Washington, DC, where he had served as president of the student body. He came to Berkeley with the intention of studying for a master's degree. But he changed his mind on arrival, and took the preliminary examination for a Ph.D. After three years of hectic preparations, he received his doctorate in child psychology at the age of 23.

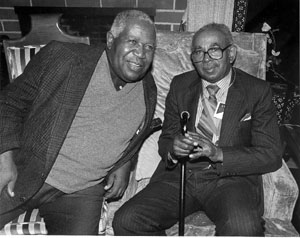

Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett (r.) with his lifelong best friend, Thomas Fleming, in 1994. One of the most influential liberal voices in San Francisco for nearly half a century, Goodlett died in 1997. In January 1999, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown led a ceremony to officially rename the address of City Hall to 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place. His Ph.D. led him to become a member of the faculty of West Virginia State College in Institute, West Virginia, the all-black undergraduate college that the state operated as part of its system of segregated public schools from kindergarten to the college level. He remained at Institute for one year before he decided to attend Meharry Medical College in Nashville, to fulfill his stated plan while at Berkeley to enter medicine and become a pediatrician. He and I had both met Dr. Legrand Coleman, a black physician, when Coleman established his medical practice in West Oakland. The three of us saw each other just about every day, and after Carlton left Berkeley, we all stayed in touch. Coleman and I encouraged him to return to his much-maligned "last frontier" -- California -- and in 1945 he answered the urging from us. He established his medical practice in San Francisco, sharing office space on Fillmore Street with Dr. Daniel Collins, a black dentist who was a faculty member at the University of California Dental School, and had a private practice. In the post-World War II era, the city suddenly found that the composition of the general population had changed. Where before the war, blacks were almost a rarity, they were now very visible. Most of them had migrated to work in the war industries located in or near the city, and most found lodging in the city. In 1944, I had become the founding editor of the Reporter, a weekly black paper. I recall attending a press conference when Roger Lapham was mayor of San Francisco (1944-48). Afterwards, he came up and asked me, "Mr. Fleming, how long do you think these colored people are going to be here?" I looked him in the eye and said, "Mr. Mayor, do you know how permanent the Golden Gate is?" He said yes. I said, "Well, the black population is just as permanent. They're here to stay, and the city fathers may as well make up their minds to find housing and employment for them, because they're not going back down South." He turned red in the face. That was the only exchange of words I ever had with him. Goodlett started making money right away as a physician, and he was very independent. Shortly after he arrived, he came to my assistance at the Reporter. When it merged in the late 1940s with another black paper, the Sun, to form the Sun-Reporter, both Goodlett and Collins supplied the money that made them joint publishers of the struggling paper, with me retaining my post as editor. Collins later gave up his share, and Goodlett remained publisher up until his death. With his acquisition of a newspaper, Goodlett launched a steady assault on racism in whatever form it took. His political activities grew ever larger -- not for the intention of personal gain, but for the inclusion of all black people in the state and nation. His name became identified as a solver of social problems. Goodlett was an able and very articulate person, who worked with the liberal community very closely, particularly with the liberal unions. In Goodlett's first year and a half in the city, he was asked by Dave Jenkins, the head of the California Labor School, to join the faculty. He accepted. The school was established by the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union. The longshoremen were regarded by many conservatives as being communists, or at least a communist front organization. So red-baiters of all hues in San Francisco started whispering that Goodlett was also a red, or if not, at least a fellow traveler. It was the Collins-Goodlett combination that organized the Democratic Party's first black club in the city. Carlton served as president of the San Francisco NAACP from 1947-49. During that time, he was driving toward the end of California Street, and a cop on a motorcycle pulled him over and said, "I've been following you for so many blocks and you ran through that red light." Goodlett said, "Why didn't you stop me before now?" So the cop asked to see his license, and said, "Well, Carlton." Goodlett said, "Listen here, I'm Dr. Goodlett to you, and you're officer to me." The cop said, "Get out of the car," and Goodlett said, "I'm not getting out of this goddamn car. You tell me why you stopped me." So the cop forced him out of the car and put handcuffs on him. He took him down to the Hall of Justice and booked him for resisting arrest or some old silly thing. When I found out about it, I went to the Hall of Justice and walked him out of there. He had to go to court the next morning. A lot of blacks heard about it, and the courtroom was jammed. The cop who made the arrest didn't dare to show up, so the charges were dropped. The cops avoided him from then on. They knew he was a professional man and that he hadn't done anything. In 1963, Carlton Goodlett built a combination medical office and newspaper office on Turk Street near Fillmore. His medical practice and the Sun-Reporter's business department were on the first floor, and the production department and a large room which could be used for private social gatherings were on the second floor. The office became one of the centers for the civil rights movement in the city. I could write a book on the subject of Carlton Goodlett, a man who always called himself the Champion of the People.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. Produced exclusively for the Columbus Free Press, this column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Fleming's 100-page book, Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934, is available for $7 plus $2 postage. Send request to tflemingsf@aol.com, or write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St #21, San Francisco CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |