|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 80 |

Black boxing champions

by Thomas C. Fleming, Jul 21, 1999 Jack Johnson was the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908 to 1915, the first black to hold that title. When he was champion, he did a lot of training in San Francisco, and in Alameda on the beach. They had championship fights in San Francisco in those days, in clubs. But in 1914, boxing was banned in California. When I began watching it in the 1920s, it was limited to four rounds. Any fight here was sort of an exhibition. They had fights every week at the Oakland Auditorium. And in San Francisco, they held them at the corner of Post and Steiner. I watched "Young Jack" Thompson fight there. He was a black man who became the welterweight champion in 1930. At that time, black boxers were allowed to fight for every title except the heavyweight, because of Jack Johnson. Between the time Johnson lost the title in 1915, and Joe Louis won it in 1937, there were only white champions, and nobody would promote a fight between them and a black challenger. In the 1920s, when Jack Dempsey was champion, there was a lot of talk about him fighting Harry Wills, a black heavyweight. There was controversy in the papers about who was the best of the two. But the promoters didn't think it would go. When Jack Johnson had the title, it looked like he was doing a lot of things to attract attention. Boxing is entertainment, and it is always to the advantage of boxers to get all the publicity they can. But I guess a lot of people didn't look at it that way. They didn't like Jack's style. Number one, he married a white woman. The government went after him and charged him with the Mann Act -- white slavery, taking a woman across a state line illegally to perform as a prostitute. They wanted to try him for that, so he fled to Paris with his wife. He had a few fights outside the United States. Then he agreed to fight Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. It was rumored that he made a deal: if he let Willard win the championship, the U.S. government would forgive him.

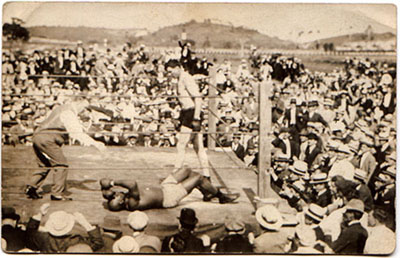

Jack Johnson lying on his back, seemingly shielding his eyes from the sun, following his controversial 26th-round knockout by Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba on April 5, 1915. There were other great black boxers at about the same time as Johnson. Joe Gans was the lightweight champion from 1901-8. Sam Langford -- they called him the Boston Tar Baby -- was a middleweight, at 160 pounds. He was fighting guys at 190, and whooping them. He never won a title, but he was a better boxer than Jack Johnson. Johnson refused to even spar with him. Langford fought in the San Francisco Bay Area a number of times, because he would travel across the country, fighting the local folk in towns. The only fights a lot of those blacks could get was against whites in a heavier weight class. After Dempsey beat Willard in 1919, the title really became valuable. I remember a fight he had with Luis Firpo, whom they called the Mad Bull of the Pampas. He weighed about 250 pounds, and he knocked out almost everybody who fought him. He had arms like telephone poles; all he'd do was march across the ring and club them down. Well, Dempsey punched harder than he did, and he couldn't get Dempsey in a corner. Every time he rushed at him, Dempsey would meet him with his fists, because he fought wide open. Dempsey made prize-fighting into first-class entertainment. He got to work with Tex Rickard, who promoted the championship fights in all divisions. Tex was the first promoter to start paying fighters $100,000 or more. He brought boxing championships to the Polo Grounds in New York City, and later to Yankee Stadium. They'd put a ring out in the middle of the field, and fill all the seats up. When Joe Louis came along, he changed the picture for black heavyweights altogether. He got to fight James Braddock for the championship because he was so damn good, and I think the media demanded that he have the opportunity. It meant money for the promoters, and the fighters too. Louis came out here in 1935 to fight a guy named Reds Barry in San Francisco, before he was champion. He knocked Barry out in the third. He'd just started boxing professionally, but he'd become a sensation. He had a long string of knockouts, and everybody wanted to see him, all over the country. The newspapers were full of it. You couldn't avoid it. I didn't go to the fight, but I went to see him when he was working out in the gymnasium in Oakland, training for the fight. You'd pay 50 cents admission to go in there and watch. And I said, "This guy's got the fastest hands I've ever seen." He never did dance; he just kept moving forward, all the time. Jack Johnson said Joe Louis wasn't that good. Well, it was a case of envy. Joe was getting the kind of adulation Jack didn't receive. And he bad-mouthed Joe, which I thought was very small on his part, because he'd had his day. Everybody loved Joe Louis. He was a simple boy of nature. Every time he won, he'd get in the ring and say, "I win Momma." He was a man of very few words. He was bright enough, but uneducated. He had two black men who managed him very cleverly, so he wouldn't affront anybody. Those guys kept him in good order. He never got in any escapades at all. Whenever Louis fought, I think every black in the United States was at home, listening to it on the radio. Everybody had radios, and we'd always go where there would be several of us together so we could talk about it. We wondered how many rounds the other guy would last. Joe fought against mostly white. I heard that some blacks became over exuberant about the fights, and acted like fools out on the streets. But out of all the fighters, there's only one to me: "I'm the greatest." He was the most articulate of any I've seen. You couldn't dislike him. He was like a big kid, full of exuberance about life. I followed Ali's career ever since the day in 1964 when he demolished the huge Sonny Liston and took away his title. Right after that, he announced his conversion to the Islamic faith, changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, and told of his joy at becoming a very vocal supporter and member of the Nation of Islam. When he was champion, he paid a visit to the Sun-Reporter office in San Francisco. He came upstairs, and I sat and talked with him. He had a lot to say. Everybody else was running in the door and looking in. That was the only time I met him. He had me in stitches laughing. I listened to some of his so-called poetry, and found him a highly intelligent and shrewd young black male. His future activities confirmed this opinion. He added a lot of color to boxing. He was a great showman, and people always wanted to see him. A lot of them were hoping somebody would knock his head off, because he was always bragging about how great he was. But he had principles, and he never deviated from them. He shocked the world when he said, "I'm Muhammad Ali. I dropped that slave name." That's all right for Muslims, but I don't see any reason for other black Americans to give themselves African names, the way some do. A lot of them got lost behind this stuff that Ron Karenga came up with. I never understood it myself. If you're going to do that, go over to Africa and live.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. Produced exclusively for the Columbus Free Press, this column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Fleming's 100-page book, Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934, is available for $7 plus $2 postage. Send request to tflemingsf@aol.com, or write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St #21, San Francisco CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |